Can you regulate aesthetics? Can economists measure it?

Those are the questions raised by historic preservation districts—areas where buildings are restricted to specific architectural styles and sizes. Their advocates say they protect the character of a city, and raise the values of the homes there. Critics say that, by restricting development, they make housing less affordable across an entire city. A new study by a group of urban researchers, including urban economist Edward Glaeser and law professor Vicki Been, looks at the experience of New York City—and tentatively finds that both sides of this debate are right.

The implications matter not just for the largest city in the US, but for urban areas around the globe.

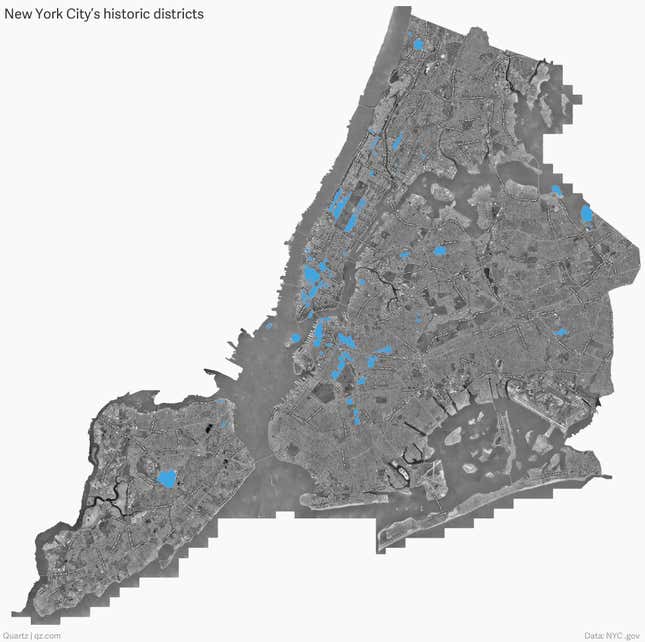

New York City has been a pioneer in historic districts, and has a significant number of them—4.8% of the city’s residential units are in protected districts, and 11.8% of the residential units in Manhattan, the city’s most expensive borough.

The researchers built a model that attempts to understand how aesthetics and protection affect home buyers and home builders—no easy task, especially when they need to control for the fact that preserved districts are often nice enough that prices might well have increased regardless of the designation.

Interestingly, historic districts in Manhattan actually reduced prices there relative to less regulated neighborhoods—probably because no matter how many billionaires you can fit into a 19th century townhouse, you can fit even more into a 21st century luxury sky-scraper.

That reflects the key finding that the value unlocked by historic preservation depends on how developed a neighborhood is relative to current zoning—if it’s already fairly close to the limits, historical preservation will increase prices, but in areas like Manhattan where landowners can build very tall buildings, the restrictions lead to lower prices.

Overall, the study found that historic districts led to higher prices, especially in the buffer zone around historic districts where developers can still build larger buildings while taking advantage of the aesthetic bonus.

But there is always a cost, and in this case, it’s a moderate reduction in construction in the historic districts relative to nearby neighborhoods. However, the authors concede that they can’t distinguish between construction decreasing in the protected districts or increases in construction in the nearby neighborhoods, so they are reluctant to say outright that historic preservation leads to decreased housing supply in cities overall.

But their model does shed some light on how city planners should think about historic districts and other kinds of preservation: ”A government that maximizes total property values will typically be more restrictive than a government that maximizes total welfare,” the authors write, “both in mandating too much preservation and in allowing too little development.” That gets at the big conflict in US housing policy: Should Americans focus on developing housing that’s affordable, or on trying to make housing as expensive as possible?